The Horses Run - Sort of

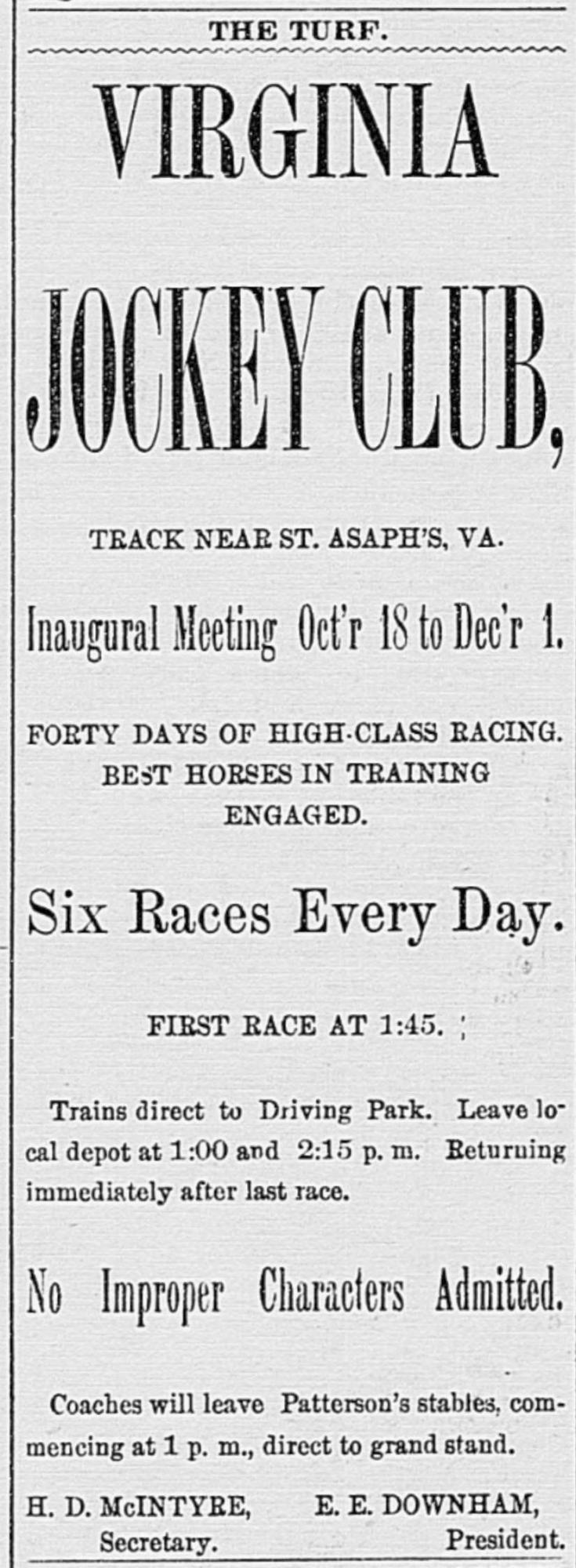

So far, so good. One last hurdle was that all racing organizations had to be registered with one of two national certifying organizations, the Jockey Club in NYC or the Western Turf Congress in Chicago. Failure to register would render a track an “outlaw” organization and severely limit its ability to attract quality horses. The Virginia Jockey Club applied to, and was accepted by, the Jockey Club in New York.

At the same time they had to negotiate the minefield of Virginia politics, sometimes with finesse, sometimes with heavy-handed lobbying. There was a vocal anti-gambling contingent in the state legislature, led by Delegate Addison Maupin. Maupin opposed all forms of gambling and was ostensibly joined in the upper house by state senator George Mushbach from Alexandria. A key difference was that while Maupin wanted all gambling made illegal, Mushbach wanted to exempt horse racing tracks and agricultural fairs. This was hardly surprising since, as was known at the time, Mushback was president of the Alexandria Gentlemen’s Driving Club. The Mushbach bill was adopted and St Asaph was off and running.

Racing started on October 18, 1894 with the first “meeting” to run to December 1. This, however, was preceded by a quite a bit of drama. First, there was considerable confusion among lawyers and law enforcement as to whether the Mushbach law allowed winter racing, that is, after December 1. JM Hill initially seemed inclined to keep racing and challenge the law, but in mid-October the Jockey Club in NY weighed in, pointing out that their bylaws also prohibited it. Representatives from Virginia went north to plead their case, but to no avail; the Jockey Club was adamant that winter racing would lead to a loss of license. Faced with that Hill capitulated and contented himself with stabling several hundred race horses from northern, colder, climes over the winter and spreading sand dredged from Cameron Run over the track to soften it.

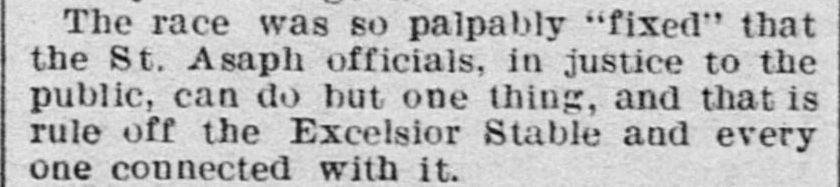

Racing resumed on May 14, 1895, but when the New York tracks opened a few weeks later much of the gambling business moved north and purse sizes were reduced. The races ran through the end of the year, but plagued with widespread allegations of cheating that caused the more honest horsemen to boycott the track. The Washington Times noted that “Dishonest jockeys, horsemen and trainers, aided by the free use of all kinds of electrical appliances, speed producing and decreasing concoctions of “dope”, and ringers galore have helped make the game one almost impossible to beat.” Fed up, the Jockey Club, led by August Belmont, suspended the Virginia Jockey Club in June.

Not wanting to be associated with a now-outlaw track, by mid-September many of the owners had taken their horses elsewhere and individually applied to New York for reinstatement. St Asaph officials predicted that most of them would return once they realized that they could not compete on the larger tracks, such as Saratoga, a telling comment on the quality of their own races by that point.

The Washington Times reports on May 19, 1895 race at the St Asaph track.

On January 3, 1896 the Virginia Jockey Club announced that it was finished racing until the spring. It proved to be permanent. There were probably about 500 horses in the stables at the track, all of them second-rate racers, and about 300 trainers, stable hands, jockeys, etc. In most cases the owners simply walked away, ceasing to pay the people and providing no food for the horses. The prior winter horses had gone unfed for days at a time and the men and boys there received only one meal a day. Things would be worse now. One departing owner was quoted as saying of his horses “They might just as well starve in Virginia as anywhere else.” Malnourished, they would then be sold for pennies on the dollar to pay creditors for what little forage they had been provided. Horse racing was over.